We just wrapped up Week 1 of my UIUC course, ECE598DA: Topics in Information-Theoretic Cryptography. The class introduces students to how tools from information theory can be used to design and analyze both privacy applications and foundational cryptographic protocols. Like many courses in privacy and security, we began with the classic one-time pad as our entry point into the fascinating world of secure communication.

We also explored another ‘tool’ for communication: the talking drum. This musical tradition offers a striking example of how information can be encoded, transmitted, and understood only by those familiar with the underlying code. In class, I played a video of a master drummer to bring this idea to life.

What Are Talking Drums?

Talking drums, especially those like the Yoruba dùndún, are traditional African hourglass‑shaped percussion instruments prized for their ability to mimic speech. Skilled drummers can vary pitch and rhythm to convey tonal patterns, effectively transmitting messages over short distances.

- Speech surrogacy: The drum replicates the microstructure of tonal languages by adjusting pitch and rhythm, embodying what researchers call a “speech surrogate” .

- Cultural ingenuity: Historically, these drums served as everyday communication tools, not merely for music or rituals but for sharing proverbs, announcements, secure messages, and more.

Here’s one of the exercises I gave students in Week 1:

Exercise: Talking drums. Chapter 1 of Gleick’s The Information highlights the talking drum as an early information technology: a medium that compresses, encodes, and transmits messages across distance. Through a communications theory lens, can you describe the talking drum as a medium that achieves a form of secure communication?

And here’s a possible solution:

African talking drums (e.g., Yoruba “dùndún”) reproduce the pitch contours and tonal patterns of speech. Since many West African languages are tonal, the drum reproduces structure without literal words.

- Encoding: A spoken sentence is mapped into rhythmic and tonal patterns.

- Compression: The drum strips away vowels and consonants, leaving tonal “skeletons.”

- Security implication: To an outsider unfamiliar with the tonal code or local idioms, the message is incomprehensible. In effect, the drum acts as an encryption device where the key is cultural and linguistic context.

There are a few entities to model:

- Source: Message in natural language (tonal West African language, e.g., Yoruba).

- Encoder: Drummer maps source to a drummed signal using tonal contours and rhythmic patterns.

- Channel: Physical propagation of drum beats across distance, subject to noise (wind, echo, competing sounds).

- Legitimate receiver: Villager fluent in both the spoken language and cultural conventions.

- Adversary: Outsider (colonial administrator, rival tribe, foreign merchant) who hears the same signal but lacks full knowledge of mapping or redundancy rules.

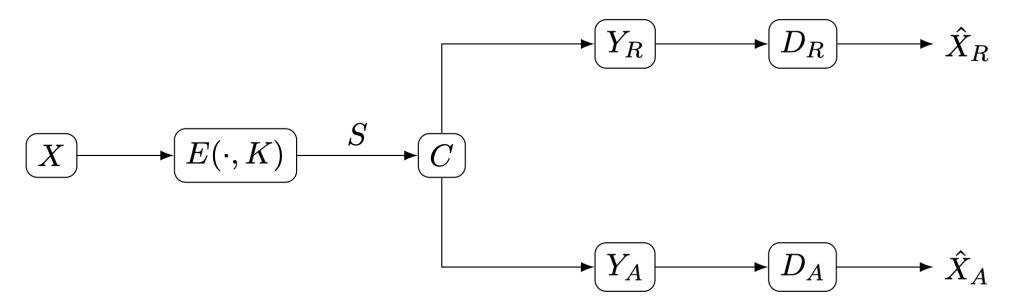

Let denote a message in a tonal language (e.g., Yoruba). A drummer acts as an encoder

mapping

to a drummed signal

, where

denotes shared cultural/linguistic knowledge (idioms, proverbs, discourse templates) known to legitimate receivers but not to outsiders. The signal

traverses a physical channel

and is received as

by insiders and as

by an adversary (outsider). Decoders

and

attempt to reconstruct

: