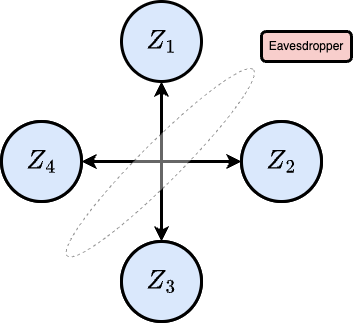

In cryptography, secret key agreement is usually framed as a two-party story: Alice and Bob want to agree on a shared secret while Eve listens. But many real systems are not two-party systems. They involve teams of devices, servers, users, or sensors that need to establish the same secret key, often in the presence of public discussion and potentially powerful adversaries. A recent paper of mine, with Benjamin Kim (lead student author) and Lav Varshney, asks a simple question:

Can ideas from coding theory and secret sharing give us a clean, scalable way to do multiterminal secret key agreement?

Our answer is yes! The paper develops a simple multiterminal key agreement scheme built from maximum distance separable (MDS) codes (specifically Reed-Solomon codes) and then analyzes its secrecy and rate through the lens of secret key capacity and multivariate mutual information (MMI). The key point is that the same threshold structure that makes Reed-Solomon codes powerful for secret sharing also makes them surprisingly natural for multiterminal key agreement.

The Big Picture

The paper sits at the intersection of three ideas.

First, there is secret sharing. In a threshold secret sharing scheme, a secret is split into shares so that any

shares can reconstruct the secret, but any fewer than

reveal nothing about it. Shamir Secret Sharing schemes (via use of Reed-Solomon codes) are a well-studied class of techniques to realize this threshold property.

Second, there is secret key agreement (SKA). In the multiterminal SKA setting, multiple parties start with correlated private observations, publicly discuss information over an authenticated public channel, and aim to end with the same shared key while leaking essentially nothing useful to an eavesdropper. The information-theoretic performance limit is measured by the secret key capacity.

Third, there is coding theory. Error-correcting codes already encode redundancy in a structured way. MDS codes are optimal in a precise sense: they achieve the maximum possible distance for their block length and dimension. That is, they give the strongest threshold-reconstruction behavior for a given amount of redundancy.

What our paper does is connect these three threads in a particularly direct way: use an MDS codeword as the object being partially distributed across terminals, then exploit the threshold property to guarantee recoverability for the legitimate users and secrecy against the wiretapper.

Why this Connection is Interesting

At a high level, secret sharing and multiterminal key agreement share many goals/targets/techniques.

In secret sharing, you start with a secret and want to distribute it safely across many users.

In multiterminal key agreement, you start with distributed private information and want users to end up with a shared secret key.

These are not identical tasks, but they share the same core geometry: some subsets of information should be enough to reconstruct, and smaller subsets should reveal nothing. The paper’s main conceptual contribution is to push this analogy far enough to get an explicit multiterminal SKA protocol out of it. (The abstract states this clearly: the work explores the connection between secret sharing and secret key agreement, yielding “a simple and scalable multiterminal key agreement protocol” based on Reed-Solomon codes with threshold reconstruction.)

The threshold semantics of MDS codes are exactly the right structure for a scalable multiterminal key agreement design.

The Model

The paper works in the standard multiterminal communication setup. There is a set of terminals , a subset

active users who must recover the final key, and possibly helpers in

. Each user has access to a private correlated source

, and everyone can participate in public discussion, which an eavesdropper also sees. The key must satisfy two conditions:

- Secrecy: the public discussion should reveal essentially no information about the key.

- Recoverability: every active user should be able to reconstruct the key from their private source and the public discussion.

The paper also recalls the standard definition of secret key capacity, the maximum achievable key rate over all allowed protocols in this model.

The Coding Idea

Now for the protocol idea.

Suppose we take a secret and pad it with additional uniform randomness, forming a vector ,

where is the actual secret and the

‘s are random pads. Then we encode

using an

Reed-Solomon code with generator matrix

, obtaining a codeword

. Each terminal receives one symbol

of this codeword, and then the protocol publicly reveals exactly

additional symbols. Since any

symbols of an

MDS code suffice to reconstruct the message, each legitimate terminal can combine its private symbol with the

public symbols and recover the full encoded message

.

This is the reconstruction side.

On the secrecy side, the protocol masks the privately delivered shares using independent random values . In the “secret-sharing-inspired” version of the scheme, terminal

has a distinct random shared value

with each terminal

, and broadcasts

.. Each intended recipient can subtract its own mask

and recover the corresponding code symbol, but the eavesdropper only sees the masked version.

So the core protocol can be summarized as follows:

- Encode the secret-plus-padding with an MDS code,

- Privately give each user one share (masked),

- Publicly reveal exactly

additional shares,

- Let each legitimate user reconstruct,

- Rely on the threshold property to ensure that the eavesdropper still stays below the reconstruction threshold.

The Main Security Statements

In the paper, we show that the eavesdropper learns nothing about the secret from the entire visible transcript.

The first main theorem captures the information-theoretic secrecy of this setup. There is also a computational variant. If one uses an IND-CPA-secure public-key encryption scheme to distribute the shares to terminals, then the protocol becomes computationally secure against PPT adversaries rather than information-theoretically secure against unbounded ones. That computational extension is practically important because it shows the scheme is not tied to idealized pre-shared masks. If you are willing to step down from unconditional secrecy to computational secrecy, you can distribute shares using standard encrypted channels.

If I had to summarize the paper in one sentence, I would say this:

It shows that MDS codes are not just a convenient implementation tool for multiterminal key agreement; they are a structural bridge between secret sharing, error correction, and SKA capacity.

For further details, take a look at the paper. Feedback/comments are welcome!