I try to always consider the classical alternative to any quantum computation or quantum information-theoretic primitive. This is a deliberate choice. I am not a pure quantum theorist in the sense of studying quantum models in isolation, nor am I interested in quantum advantage as an article of faith. Rather, my goal is to delineate (as precisely as possible) the boundary between what classical and quantum theories can guarantee, especially when privacy guarantees are composed over time, across mechanisms, or between interacting systems.

In the context of privacy, composition is where theory meets reality: real systems are never single-shot. They involve repeated interactions, adaptive adversaries, and layered mechanisms. Quantum information introduces new phenomena (entanglement, non-commutativity, and measurement disturbance) that complicate classical intuitions about composition. At the same time, classical privacy theory has developed remarkably robust tools that often remain surprisingly competitive, even when quantum resources are allowed.

The guiding question of this post is therefore not “What can quantum systems do that classical ones cannot?” but rather:

When privacy guarantees are composed, what genuinely changes in the transition from classical to quantum. And what does not?

By keeping classical alternatives explicitly in view, we can better understand which privacy phenomena are inherently quantum, which are artifacts of modeling choices, and which reflect deeper structural principles that transcend the classical vs. quantum divide.

Classical Composition of Differential Privacy

Recall the definition of differential privacy:

Approximate Differential Privacy

Let denote the data universe and let

be the set of datasets.

Two datasets are called neighbors, denoted

, if they differ in the data of exactly one individual.

A (possibly randomized) algorithm is said to be

-differentially private if for all neighboring datasets

and all measurable events

,

.

It has been shown in a few references/textbooks that basic composition holds for differential privacy. We recall the statement:

Theorem (Basic sequential composition for approximate differential privacy)

Fix . For each

let

be a (possibly randomized) algorithm that, on input a dataset

, outputs a random variable in some measurable output space

.

Assume that for every ,

is

-differentially private.

Define the -round interactive (sequential) mechanism

as follows: on input

, for

, it outputs

where denotes the

th mechanism possibly chosen adaptively as a (measurable) function of the past transcript

.

Let denote the full transcript in the product space

.

Then is

-differentially private.

In particular, if and

for all

, then

is

-differentially private.

What happens in the quantum setting?

Composition of Quantum Differential Privacy

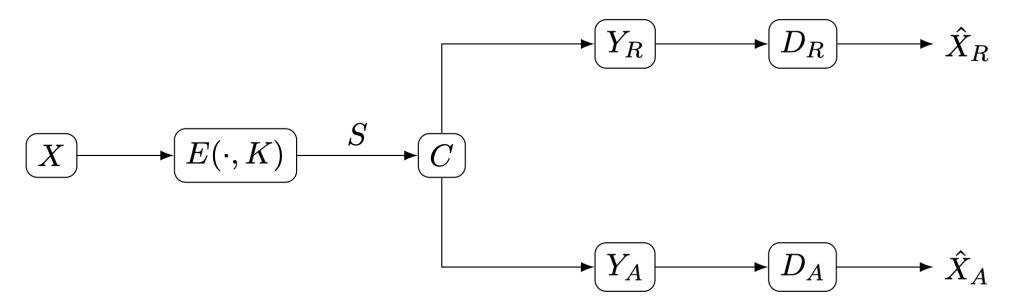

A central “classical DP intuition” we have already set up is: once you have per-step privacy bounds, you can stack them, and in the simplest form the parameters add. e.g., adds across rounds. In the quantum world, however, DP is commonly defined operationally against arbitrary measurements; and this makes the usual classical composition proofs, which rely on a scalar privacy-loss random variable, no longer directly applicable.

In a recent work, Theshani Nuradha and I show two complementary points, one negative (a barrier) and one positive:

- Composition can fail in full generality for approximate QDP (POVM-based).

We show that if you allow correlated joint implementations when combining mechanisms/channels, then “classical-style” composition need not hold: even channels that are “individually perfectly private” can lose privacy drastically when composed in this fully general way. - Composition can be restored under explicit structural assumptions.

Then we identify a regime where you can recover clean composition statements: tensor-product channels acting on product neighboring inputs. In that regime, we propose a quantum moments accountant built from an operator-valued notion of privacy loss and a matrix moment-generating function (MGF). - How we get operational guarantees (despite a key obstacle).

A subtlety we highlight: the Rényi-type divergence we consider for the moments accountant does not satisfy a data-processing inequality. Nevertheless, we prove that controlling appropriate moments is still enough to upper bound measured Rényi divergence, which does correspond to operational privacy against arbitrary measurements. - End result: advanced-composition-style behavior (in the right setting).

Under those structural assumptions, the paper obtains advanced-composition-style bounds with the same leading-order behavior as in classical DP. i.e., you can once again reason modularly about long pipelines, but only after carefully stating what “composition” means (i.e., joint, tensor-product, factorized) physically/operationally in the quantum setting.

Check out the paper. Feedback/comments are welcome!