As I write this blog post, I just received news that the U.S. is designating Nigeria as a ‘country of particular concern’ over Christian persecutions. I cannot think of any other country with such a large population but (almost) equal representation of Christians and Muslims. Since before I was born, this has caused a lot of friction but somehow the country has survived all that friction (thus far!). But the friction stems from tradeoffs of having such religious heterogeneity, a topic of its own discussion. But in this post, I’ll focus on the high levels of mathematical tradeffs.

There’s something deeply human about lower bounds. They’re not just mathematical artifacts; they’re reflections of life itself. To me, a lower bound represents the minimum cost of achieving something meaningful. And in both life and research, there’s no escaping those costs.

The Philosophy: Tradeoffs Everywhere

Growing up, I was lucky enough to have certain people in my family spend endless hours guiding me: helping with schoolwork, teaching patience, pushing me toward growth. Looking back, I realize these people could have done a hundred other things with that time. But they (especially my mum) chose to invest it in me. That investment wasn’t free. It came with tradeoffs, the time she could never get back. But without that investment, I wouldn’t be who I am today.

That’s the thing about life: everything has a cost. In 2022/2023, I could have focused entirely on my research. But instead, I poured my energy into founding NaijaCoder, a technical education nonprofit for Nigerian students. It was rewarding, but also consuming. I missed out on months of uninterrupted research momentum. And yet, I have no regrets! Because that, too, was a lower bound. The minimum “cost” of building something (hopefully) lasting and impactful.

Every meaningful pursuit (i.e., love, growth, service, research) demands something in return. There are always tradeoffs. Anyone who claims otherwise is ignoring the basic laws of nature. You can’t have everything, and that’s okay. The beauty lies in understanding what must be given up for what truly matters.

Lower Bounds in Technical Domains

Mathematicians talk about lower bounds as the limits of efficiency. When we prove a lower bound, we’re saying: “No matter how clever you are, you can’t go below this.” It’s not a statement of despair: it’s a statement of truth.

Lower bounds define the terrain of possibility. They tell us what’s fundamentally required to solve a problem, whether it’s time, space, or communication. In a strange way, they remind me of the constraints in life. You can’t do everything at once. There’s a cost to progress. To prove a good lower bound is to acknowledge that reality has structure. There’s an underlying balance between effort and outcome. It’s an act of intellectual honesty: a refusal to pretend that perfection is free.

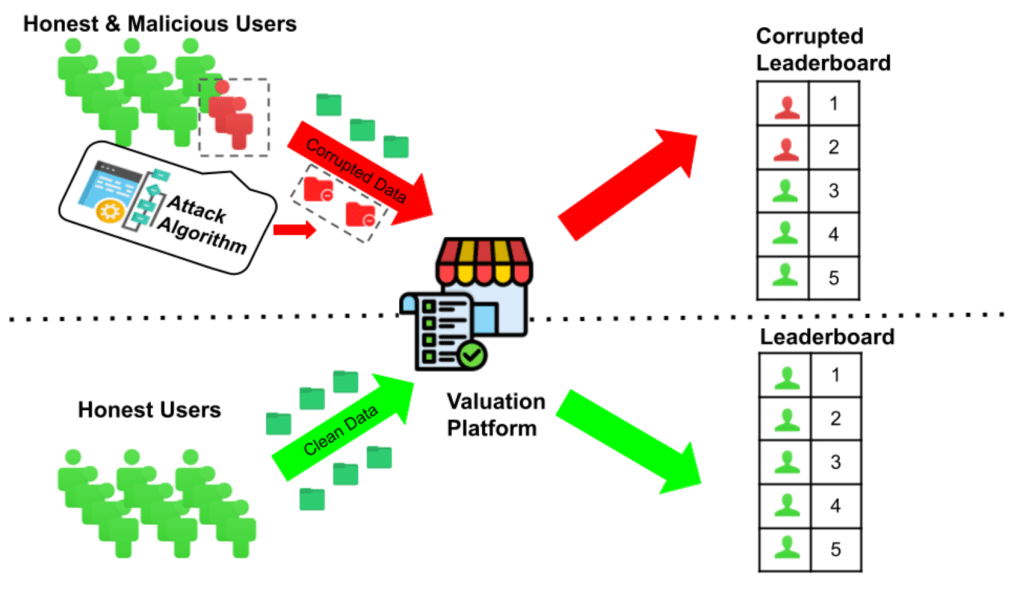

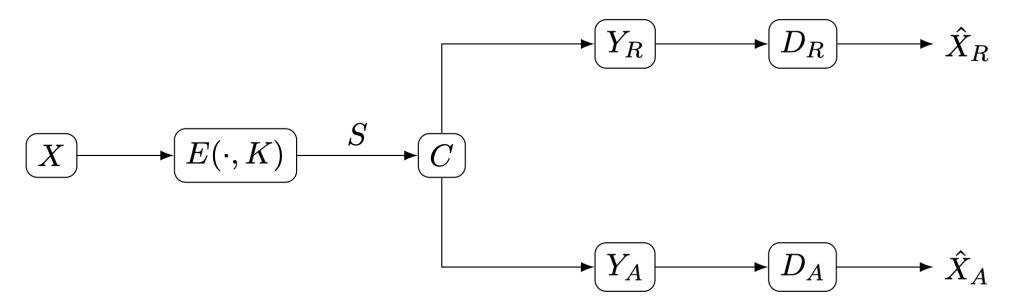

Nowhere do these tradeoffs feel more personal than in privacy. In the quest to protect individual data, we face the same universal truth: privacy has a price. If we want stronger privacy guarantees, we must give up some accuracy, some utility, some convenience. In differential privacy, lower bounds quantify that tension. They tell us that no matter how sophisticated our algorithms are, we can’t perfectly protect everyone’s data and keep every detail of the dataset intact. We must choose what to value more — precision of statistical estimates or protection.

These aren’t technical inconveniences; they’re moral lessons. They remind us that every act of preservation requires some loss. Just as my mother’s care required time, or NaijaCoder required research sacrifices, protecting privacy requires accepting imperfection.

Acceptance

The pursuit of lower bounds (in research or in life) is about humility. It’s about recognizing that limits aren’t barriers to doing good work; they’re the context in which doing good becomes possible.

Understanding lower bounds helps us stop chasing the illusion of “free perfection.” It helps us embrace the world as it is: a world where tradeoffs are natural, where effort matters, and where meaning is found not in escaping limits but in working within them gracefully.

So, whether in mathematics, privacy, or life, the lesson is the same: there are always tradeoffs. And that’s not a tragedy; it’s the very structure that gives our choices value.

I hope these ideas shape how I live, teach, and do research going forward. In my work on privacy, I’m constantly reminded that (almost) every theorem comes with a cost and that understanding those costs makes systems more honest and human. In education, through NaijaCoder, I see the same principle: every bit of growth for a student comes from someone’s investment of time and care.

Developing lower bounds isn’t just a mathematical pursuit. It’s a philosophy of life, one that teaches patience, realism, and gratitude. The world is full of limits, but within those limits, we can still create beauty, meaning, and progress: one bounded step at a time.